Printing with Sunlight

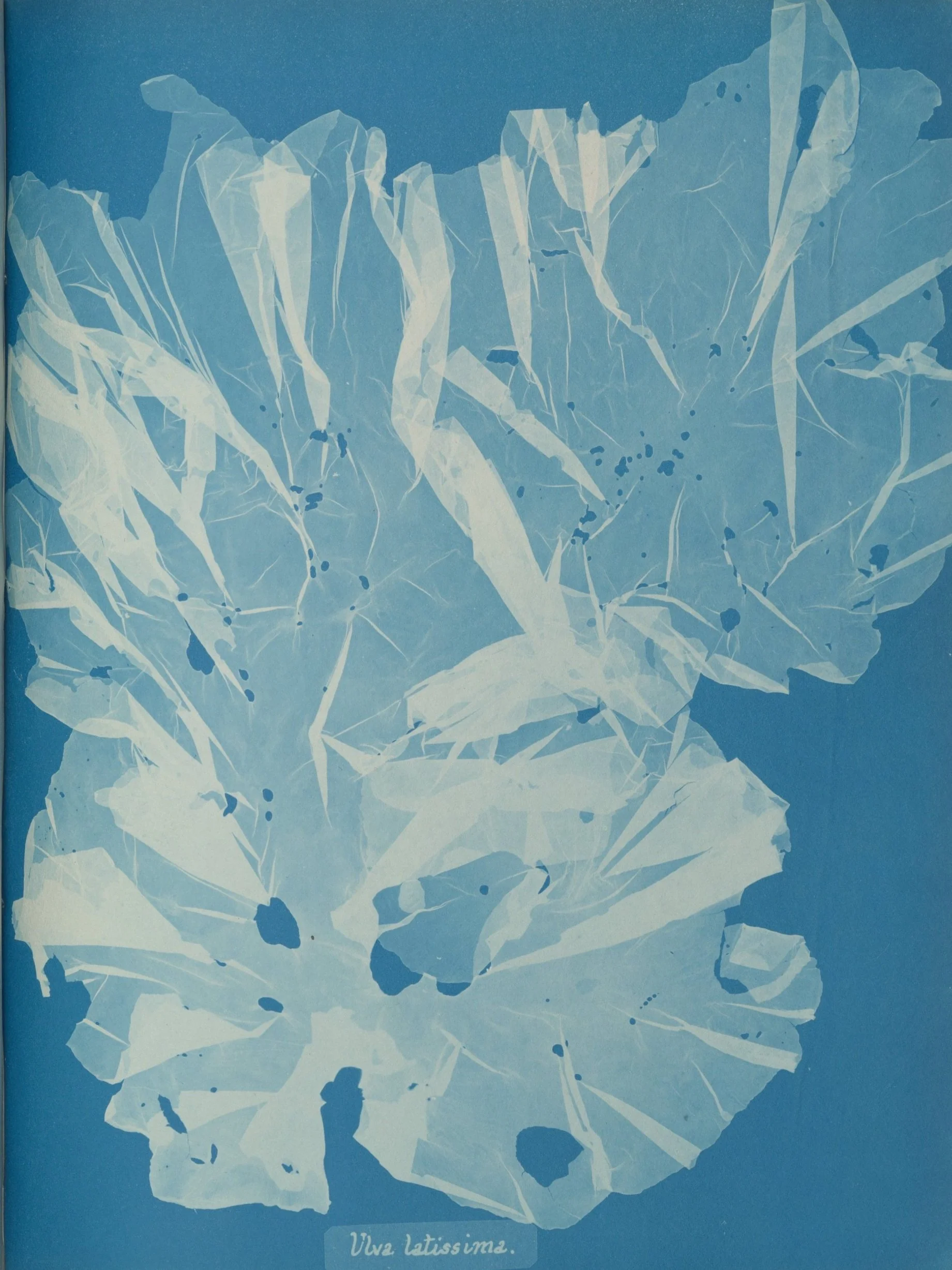

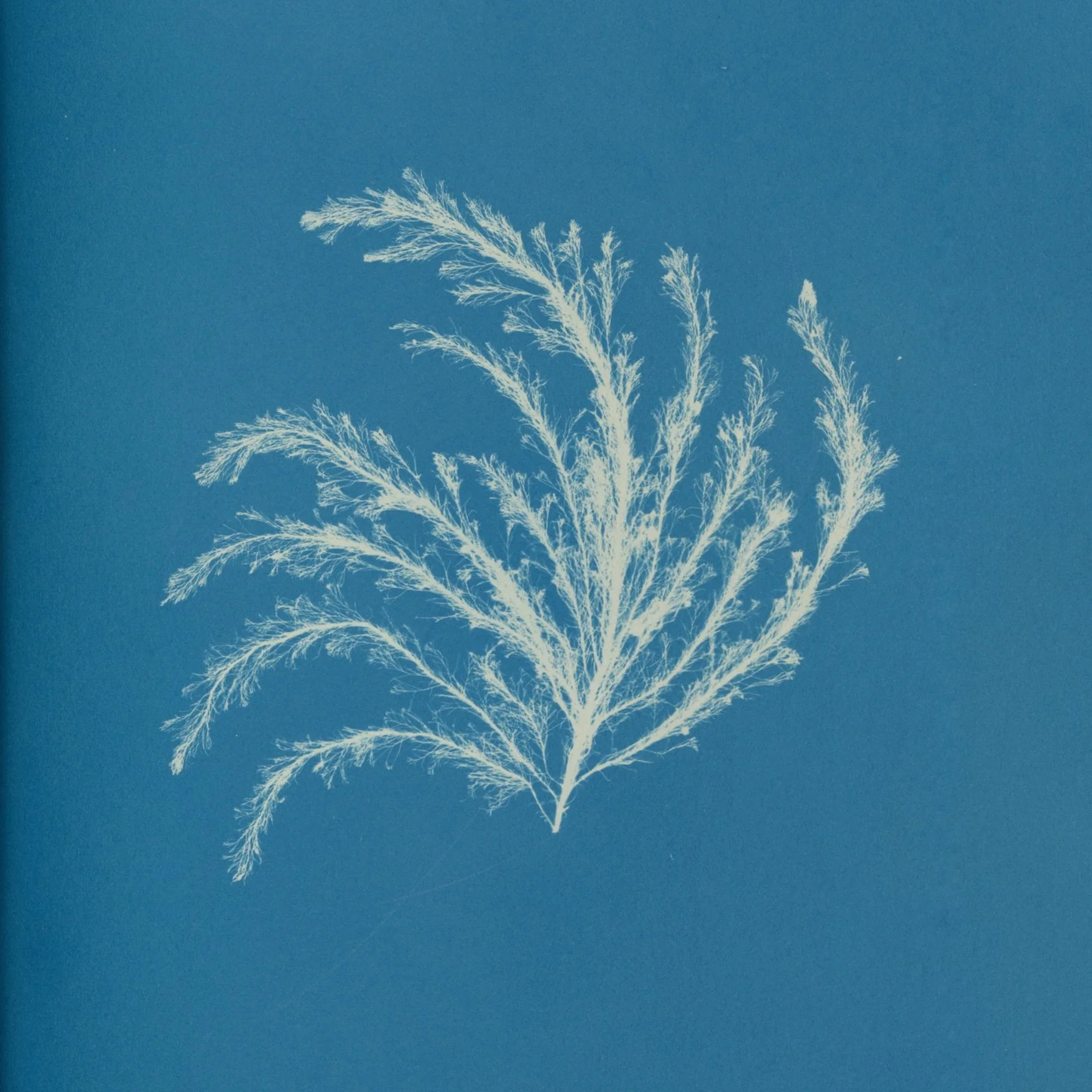

In 1843 an English botanist named Anna Atkins (born Anna Children in 1799) created what has become known as the world’s first photographic book when she used cyanotype to make images of algae. The impressions created are life-size and record the precise outline of the specimens. They also reflect the translucency of the algae, with areas that permitted more sunlight to reach the paper developing a darker colour than the areas which were more opaque.

Anna was the daughter of John George Children (1777-1852), a prominent scientist and the first president of the Royal Entomological Society. Anna’s mother died when she was still a baby, so her father represented the greatest influence in her life growing up. She assisted him in the 1820s by producing illustrations for his English translation of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s Genera of Shells, but Anna’s particular interest was botany, and it was a serious one; in 1839 she was elected a member of the Botanical Society of London, one of the few societies open to women.

As well as making a place for herself in the field of botany, Anna’s curiosity and social connections brought her into contact with the very latest developments in the emerging art of photography.

She and her husband, John Pelly Atkins (1790-1872), were acquainted with William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) and Sir John Herschel (1792-1871), both pioneers of early photography.

It was Herschel who invented the cyanotype process following his investigations into the light-sensitivity of various chemical and organic substances. He made his findings public in June 1842, presenting a paper to the Royal Society entitled “On the Action of the Rays of the Solar Spectrum on Vegetable Colours, and on Some New Photographic Processes”. Anna was following this research closely, and she lost little time in experimenting with the cyanotype process herself, gaining enough expertise and confidence to embark on creating a photographic book of British algae within a year.

“I have lately taken in hand a rather lengthy performance” she wrote to a friend in October 1843, and she was not exaggerating. Anna carried out the cyanotype process herself, preparing and exposing each page individually. With around 400 plates in each book, and an estimated 15-20 copies of the book produced (there are 16 known copies), she had to personally produce thousands of high-quality cyanotypes.

From the perspective of a society saturated with photographic images, it is easy to overlook the novelty and innovation of Anna’s use of cyanotype to illustrate a scientific book. For the first time the illustrations were photographic impressions of the plants themselves, rather than illustrations by an artist, and there would have been a real fascination around the images, which, despite their simplicity, have a unique quality which underlines the living nature of their subjects. They appear ghostly and shadow-like, the marks of an entity that has left a layer of itself behind.

By reducing the subject to a monochrome image, the cyanotypes highlight the shape and structure of the algae or plants, and can capture the contrast between the finest, tissue like membranes and the solid, opaque elements of a specimen. The process seems especially appropriate for marine life as the algae seem to calmly float on the sea of blue behind them.

Anna sought no fame or fortune with her book, which was mainly distributed among friends and acquaintances with an interest in either botany, photography, or both. While it was gratefully received by those within her prominent circle, it did not make waves within the wider scientific community, and at one point the story of Anna Atkins seemed at risk of fading away. In fact, when the prints were discussed in an article in the late 1880s, the author had no idea of the creator’s real identity, and surmised that the initials A.A. must have stood for “Anonymous Amateur”.

Thankfully Anna Atkins’ name and story has not been lost to anonymity. In fact her legacy is significant in manifold ways; she was a pioneer of photography, a serious botanist and she had the initiative to create her own opportunities in a world which did not seek out women’s contributions. Art historians are also interested in the aesthetics of the prints, whose striking compostions and contrasting colours have given them lasting appeal.

The result is that Anna’s “lengthy performance”, never intended to be lucrative, has created an extremely valuable body of work, which, when it appears on the private market, attracts much interest. Single plates sell in excess of £5,000 and an original volume once belonging to the scientist Robert Hunt (1807-1877) was sold in 2004 for well over £200,000.